Cauldron of Stories

Lesson Objective: Students will examine a manuscript on astrology to learn about the advancement of Persia’s astronomical sciences.

Homira Pashai 7-25-2020

Studies on Persianate Manuscripts, Arts, and Literature

Illustration: Courtesy of the Bodleian Library, BnF Research Library, MIA Library.

Source: Schmidl Petra, “Mirrors of the Stars: The Astrolabe and What It Tells About Pre-Modern Astronomy in Islamic Societies,” in Sonja Brentjes Sonja, Edis Taner and Richter-Bernburg Lutz, 1001 Distortions How (Not) to Narrate History of Science, Medicine, and Technology in Non-Western Cultures, pp.173-189. Hafez Ihsan, Stephenson F. Richard, and Wayne Orchiston, Abdul Rahman al-Sufi and His book of the Fixed Stars: A Journey of Re-discovery, 2011.

Kitab suwar al-kawakib al-thabita

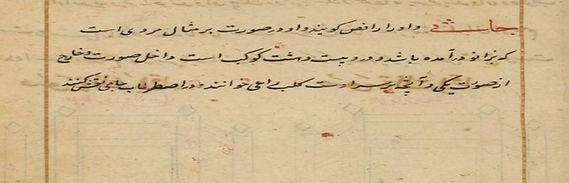

The manuscript, Suwar al-kawakib al-thabita صور الکواکب الثابته , was written by Abdul Rahman al-Sufi عبدالرحمان صوفی . Al-Sufi (903-986 C.E.) was born in the city of Rayy, southeast of Tehran. He is known as the great patron of astronomy and a renowned scholar. Kitab Suwar al-kawakib is based on Ptolemy’s Almagest, al-Battani’s star catalog, and Abu Hanifa Dinawari’s book on old Arabic astronomical traditions. Al-Sufi also made an observatory in Shiraz and wrote a Zij (astronomical handbook) and other treatises on astrology, mathematics, trigonometry, and astrolabe. His work on astrolabe comprises 1760 chapters, in which each chapter examined a problem and solved it with the help of astrolabe.

Kitab-i Suwar al-Kawakib al- thabita, The Book of Fixed Stars, was initially written in Arabic and included 55 astronomical tables with star charts. The constellations were discussed in detail with respect to the Northern, Zodiac, and Southern constellations. The manuscript also examined descriptions of nebulae and popular astronomic lore of the time. The illustrations of the Kitab-i Suwar are depicted in mirror-image versions, which means each constellation is depicted twice. “The first represents the constellation as it is seen in the sky from the earth (or the so-called sky-view); the second record the constellation as it is seen from outside the sphere of the fixed stars, or as it would appear on the surface of a celestial globe (the so-called global view).” At the end of his treatise, al-Sufi elaborates on the illustrations and their pedagogical values. According to him, mirror-image paintings are designed to assist astronomy students in memorizing and mapping the constellations in the sky. Al-Sufi also made the first known observation of the Andromeda galaxy, a group of stars outside the Milky Way. Al-Sufi is known as Azophi to the West.

In the mid-1250s, King Alfonso X el Sabio, the Learned, commissioned the translation of a series of books from Arabic. Among them, the Libro de las figuras de las estrellas fixas, which was completed in 1278 in the city of Burgos, was the adoptive translation of the Kitab-i Suwar al-Kawakib al- thabita. Thus, al-Sufi’s work was translated into the Castilian language.

https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b8432266z/f99.item.r=Kit%C4%81b.zoom

https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/446297

https://www.wdl.org/en/item/2484/

Astrolabe:

“Once upon a time, Ptolemy rode along on his mount while holding an armillary sphere in his hand. Armillary spheres are three- dimensional, simplified spherical models of the universe, rather cumbersome to take along. The inevitable happened. Ptolemy dropped the armillary sphere. The animal trod on the instrument and flattened it. The astrolabe was invented. Although the reality is not as simple as this amusing story suggests, the astrolabe is a two-dimensional, flat model of the three-dimensional world. At the beginning of the 9th century, al-Khwarizmi (Baghdad c. 800-847) wrote extensively on the astrolabe, and one century later, al-Sufi contributed his treatises on the astrolabe, including 1760 chapters.”

“an astrolabe presents a hand-held two-dimensional model of the three-dimensional universe that is usually small enough to put in a pocket. These circular portable objects, usually made of brass and palm- to cartwheel-sized, often display skilled craftsmanship and advanced knowledge of celestial movements.”

“It simulates the movement of celestial objects around a terrestrial observer and may be used for calculation, observation, and timekeeping. As a two-dimensional model of the universe, the astrolabe requires two major parts, one representing the celestial part, the starlit sky, and one representing the terrestrial part, the observer’s position on earth.”